Stories of caregivers who foster personal transformation

Program scp • Half-hour segments

CDs available via special order. HumanMedia ®

Also available on our Podcast

Program scp • Half-hour segments

CDs available via special order. HumanMedia ®

Also available on our Podcast

Here’s how to subscribe to The Spiritual Care Podcast!

Please help us improve by taking our 2-minute Survey (click tab above)

On The Spiritual Care Podcast you’ll hear stories of caregivers (chaplains, nurses, social workers and many others). They provide spiritual support for people in need, and often in distress. They’re trained to be inclusive, not exclusive.

These professionals serve in multiple venues, including hospitals and hospices, colleges, the military, prisons, retirement communities, first-responder services, community organizations and other settings. They face a range of social concerns: diversity, war and peace, health care, people who’ve been marginalized, families in crisis, etc.

As caregivers, they offer a sympathetic, non-judgmental ear to people encountering times of challenge, unease and sometimes loss of meaning. Our podcast explores the skills they bring to the profound act of listening.

The Spiritual Care Podcast, with Humankind host David Freudberg, is non-sectarian and features voices from a variety of faith traditions and walks of life. We also honor the many people on a spiritual – but not necessarily religious – journey.

Our stories may be of interest to anyone wishing to learn more about how to listen and care. This series may appeal to diverse listeners: spiritual congregations, social workers, medical professionals, theologians, nonprofit leaders, academic administrators and school guidance counselors, military members, human resources professionals, social activists representing vulnerable communities, and participants in other organizations.

The heart of our podcast is stories of personal transformation, as experienced in the lives of the people cared for — and the caregivers themselves. Our aim is to acquaint listeners with the practice of spiritual care and to stimulate reflection about the inspiring stories presented.

Here’s how to subscribe to The Spiritual Care Podcast!

|  |  |

| ||

|

Part 1 | Interfaith Understanding on Campus

We hear from Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN) campus chaplains and students, representing different traditions, on the challenge of promoting interfaith understanding in a complicated an diverse world.

Part 2 | Safe Place in a War Zone

We profile a military chaplain who served in Afghanistan and who has been absorbed by questions of war and peace — and who ultimately resigned from his role as an army chaplain over American drone policy.

Part 3 | Caring for People at the End of Life

We hear from remarkable professionals who accompany — and learn from — people in their their final chapter of life.

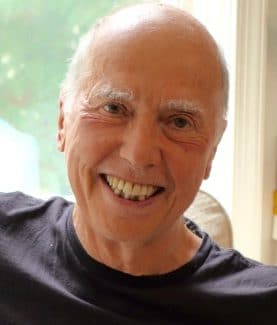

Bonus | Hospice Doc Joel Bauman

Joel Bauman, MD, a geriatrician now working in a hospice, describes ways that physicians are called to provide compassionate support and sometimes spiritual care of dying patients.

Vanderbilt Office of the University Chaplain & Religious Life staff along with affiliated chaplains: (Seated L-R) Imam Osama Bahloul, Rabbi Shlomo Rothstein. (Standing L-R) Rev. Shantell Hinton, Rev. Mark Forrester, Rev. Lindsay Groves.

We hear from chaplains and students on a college campus (Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennesee) with a long tradition of promoting dialogue among various groups. How can chaplains act as bridges between people of different traditions? What are the teachings of love for neighbor found in all great religious philosophies? What can we learn from potentially rich exchanges honoring diversity? How can students be encouraged to ’stretch out’ and discover new truths. How can we face and mitigate the prejudices and preconceptions that most people carry with them? And what role can interfaith service activities play in breaking down barriers?

Beyond just tolerating other people’s views, and other people’s experiences, we can find a way to relate to them, and to respect them for what they are, and to embrace them, in a sense, and see them on equal footing.”

— Vanderbilt Univ. student Shawn Kerry

Rev. Chris Antal, a Unitarian Universalist minister in the town of Rock Tavern, New York, was drawn to service in response to the attacks of 9/11. He entered military chaplaincy partially as a way to help soldiers who are prone to harming themselves in the wake of war. He also wanted to bring a “liberal voice into a very conservative chaplaincy,” consistent with the commitment of his tradition of acceptance for people representing different faiths and sexual orientation backgrounds.

Rev. Chris Antal, a Unitarian Universalist minister in the town of Rock Tavern, New York, was drawn to service in response to the attacks of 9/11. He entered military chaplaincy partially as a way to help soldiers who are prone to harming themselves in the wake of war. He also wanted to bring a “liberal voice into a very conservative chaplaincy,” consistent with the commitment of his tradition of acceptance for people representing different faiths and sexual orientation backgrounds.

In this profile, Rev. Antal explores how he was drawn to faith-based engagement with indigenous religious leaders, where he was stationed at Kandahar Air Base. “I was uniquely equipped to engage in interfaith dialogue” with Muslims. But what’s it like to be a spiritual presence in a war zone? What’s the duty to honor the lives of human beings who die in war, whether from your side or the “enemy”? Rev. Antal grew disenchanted with the U.S. military policy of deploying unmanned aircraft (drones), which are often associated with civilian casualties. In 2016, he resigned in protest from his commission as a chaplain in the Army Reserve and, after a Congressional inquiry, received an honorable discharge. We end this episode with an excerpt of Rev. Antal’s moving sermon about modern war.

I was challenged with the question, ‘Why, and for what?’ And that question came to me from the people I was serving as the chaplain, in most cases. It’s a question that I’d asked myself… I wasn’t the chaplain who was going to give the Army answer, or the religious answer even, per se. I never saw spiritual care as about helping anyone feel good. Spiritual care is, for me, about living well. And living well means at times holding appropriate pain, including moral pain like guilt, and regret.”

I was challenged with the question, ‘Why, and for what?’ And that question came to me from the people I was serving as the chaplain, in most cases. It’s a question that I’d asked myself… I wasn’t the chaplain who was going to give the Army answer, or the religious answer even, per se. I never saw spiritual care as about helping anyone feel good. Spiritual care is, for me, about living well. And living well means at times holding appropriate pain, including moral pain like guilt, and regret.”

— Rev. Chris Antal, Army chaplain (ret.)

Rev. Beth Loomis

At the end of life, when most people need medical care and emotional comfort, some turn also to chaplains for spiritual support. In this episode, we hear from two chaplains in Massachusetts: Nancy Small, a Catholic oblate serving patients near Worcester; and Rev. Beth Loomis, Director of Pastoral Care and a United Church of Christ minister, based at Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge. What are the challenges of serving those facing their final chapter? How do chaplains comfort people as they try to make sense of the kaleidoscope of their life experiences, including joys and regrets? How do hospice staff, including nurses and social workers, affirm that everyone’s life has worth and meaning?

We also hear the candid reflections of a dying patient, Brian Noone, recorded with his devoted wife Rosalie by his side. Listen to a beautiful rendition of Blessed Quietness, a hymn sung by the Hallowell Singers, a Vermont-based chorus that performs in the rooms where hospice patients stay.

It’s very natural, at that point in life, to start to look back on life, and ask questions about, “What has my life meant?” I remember being told once that everyone needs to know that their life has mattered, that their life has had meaning.”

It’s very natural, at that point in life, to start to look back on life, and ask questions about, “What has my life meant?” I remember being told once that everyone needs to know that their life has mattered, that their life has had meaning.”

— Nancy Small, hospice chaplain

‘T.Y.'(center), social worker Larry Clum (R) with host David Freudberg

We visit a shelter at Seattle’s Mission for a rich exchange with a formerly homeless man who feels the spiritual care he received from mental health workers helped him develop the ability to transition into housing. We hear from a social worker, Larry Clum, who explores what it means to companion homeless people without an intent to “fix” their problem. Also, several chaplains reflect in-depth on the experience of connecting with people who are facing challenges related to mental health, addiction and homelessness. Included are comments by Kae Eaton of the Mental Health Chaplaincy, Rev. Jonathan Neufeld, community minister at Seattle Mennonite Church, and Rev. Beverly Hartz, with the Veterans Administration Puget Sound Health Care system.

Most of us, are lucky enough to have many things that ground us into our identity. You know, our families, our friends, our vocations, our jobs, our homes. And when we find people that have severed ties with those grounding moments, they often lose themselves in the process too. So if we can look at them not as the other, but as ourselves, if I can see myself in you, then we start to create a reality actually for both of us. It’s not a one-way street; it’s a gift that travels in both directions.”

— Rev. Beverly Hartz, Vets Admin. Puget Sound Healthcare System in Seattle

(L-R) Mental Health Chaplaincy associates: Larry Clum, Rev. Beverly Hartz, Kae Eaton, Rev. Jonathan Neufeld

Sue Best, palliative care social worker, Oregon Health and Science University

Melissa Stewart, senior clinical social worker at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York

Among the hundreds of thousands of social workers currently serving in the United States and beyond, some see their role, in part, as spiritual care providers on a non-denominational basis. Rooted in the philanthropic movements of the 1800s, social work developed from charities known as benevolent associations, which sprang up to serve the urban poor. These were complemented by publicly supported poor houses, called “alms-houses” as well as “settlement houses”, pioneered by the legendary Jane Addams, who sought to express what she saw as a spiritual calling. An agenda of social reform naturally harmonized with a commitment to faith.

In this segment, we hear the stories of two contemporary hospital social workers, Sue Best, an Oregon-based palliative care social worker and Melissa Stewart, senior clinical social worker at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. They describe encounters with patients who are looking for a way to explore important life questions that can arise in times of challenge.

For me spirituality is the core of each person, their foundational beliefs, and values…And whether you are a devout Muslim, Jew, Christian, or a person of good will, we are all spiritual beings, because we all make sense of life, in some way, but we may express it very differently. So I think that whenever someone faces a crisis, or for the people I see with serious or traumatic illness, it comes to the core of who they are.”

— Sue Best

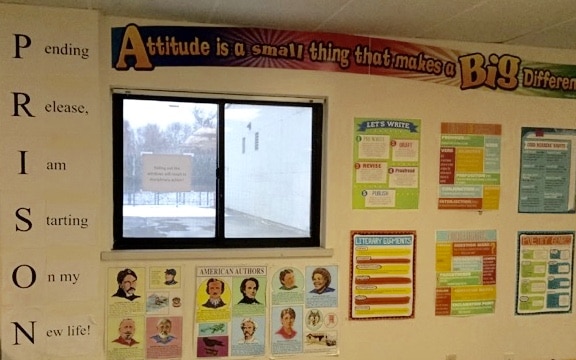

The United States incarcerates more people than any other nation in the world. Federal and state prisons and county jails hold around two million prisoners. Another five or so million people are on probation or parole. Some in this diverse population are dangerous and apparently don’t seek rehabilitation to a more productive life. For many others, though, incarceration is a forced opportunity for self-examination and positive change – a process that can be supported and stimulated by spiritual care providers. In this segment, we explore in-depth the experiences of two chaplains: Paul Shoaf-Kozak, a Christian social justice advocate who oversees the chaplaincy department at the Essex County Correctional Facility in Middleton, Massachusetts, northeast of Boston; and Genko Kathy Blackman, a Buddhist teacher who has long visited jails around the Seattle area. We also hear from two prisoners about their faith journeys while behind bars.

People would say, ‘Oh, you’re such a tiny little woman, you know, and you’d be going into a men’s prison, and aren’t you frightened?’ And I was a little bit, just because it was unknown. But when I began to go in, and meet people, and work with them, both the officers, the corrections officers and the inmates, all of that really kind of drops away, because they’re just people with the same kind of questions, looking for the same kind of answers as anybody on the outside.”

People would say, ‘Oh, you’re such a tiny little woman, you know, and you’d be going into a men’s prison, and aren’t you frightened?’ And I was a little bit, just because it was unknown. But when I began to go in, and meet people, and work with them, both the officers, the corrections officers and the inmates, all of that really kind of drops away, because they’re just people with the same kind of questions, looking for the same kind of answers as anybody on the outside.”

— Gengko Kathy Blackman

Even if the person is isolated to their solitary confinement cell, if they encounter someone on the other end of the door who is nonthreatening, who is disarming, who gives them permission to be their honest self, in ten to fifteen minutes, you know, we could have a profound conversation.”

Even if the person is isolated to their solitary confinement cell, if they encounter someone on the other end of the door who is nonthreatening, who is disarming, who gives them permission to be their honest self, in ten to fifteen minutes, you know, we could have a profound conversation.”

— Paul Shoaf-Kozak

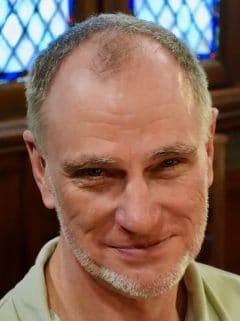

Ian Wheatley

Guy Chapdelaine

We explore the duties and challenges of military chaplains from two nations: Britain and Canada. Ian Wheatley, recorded at the Defence Ministry in Westminster, London, serves as Chaplain of the Fleet of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Sailors bring to chaplains concerns regarding family back home, as well as moral questions about warfare. We hear how seamen and women have wrestled with humanitarian problems like the recent Middle Eastern migrant crisis that spilled into Europe, sometimes with tragic results. In such circumstances, understandable questions about truth and God often arise.

Next, we visit with Padre Guy Chapdelaine, a soft-spoken Canadian who currently serves as Chaplain General of the Canadian Armed Forces, directing about 400 chaplains from diverse denominations. He sees his calling primarily as a “ministry of presence”: to be there, to be open, to hear what people have to share. And with increasing diversity in society, connecting with people of different religions is an essential skill needed to promote harmony. If people are grounded in their own beliefs, it becomes easier, he says, to enter into a healthy relationship with others.

I really struggle with trite religious answers, because I just don’t think that works. I like, if I can, to be able to get to a place in a conversation that we may scrape away a few layers and get down to the concept that in spite of what we see happening and unfolding in front of us, that in spite of all that that I understand, and I am able to own that God loves me. That’s a wonderful thing, if we can get to that place. But sometimes, as you know, that’s a difficult place to get to in one leap.”

— Rev. Ian Wheatley,Chaplain of the Fleet, British Royal Navy, Archdeacon in the Anglican Church

I would like to be a peacemaker in my life. But I believe that it’s also the gifts I receive in my life. I like to build bridges. In our world we need to work together because the challenges are so important. And the world is changing so much, we need to adapt very quickly, we need to work together. We cannot just work in our specific country.”

— Padre Guy Chapdelaine,Chaplain General, Canadian Armed Forces

At the typical nursing station of today’s hospitals, it can sometimes seem like high-tech medical machinery supersedes a personal connection between the patient and nurse or other health care professional. But for many caregivers, that one-to-one relationship is the essence of their service. This episode of The Spiritual Care Podcast considers how connections can uplift the patient being cared for, as well as nurses – who spend more time with patients than other medical professionals. It also can help to sustain and revitalize nurses, who often are called to their work through a powerful drive to serve people.

How does a caring relationship with patients help them feel less alone while undergoing a health crisis? When is it appropriate for caregivers to show personal emotion at a moment of vulnerability for the patient? How can nurses respond to the spiritual needs of patients?

We hear from Connie Delaney, Dean of the School of Nursing at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. She’s a leader in the movement to reinforce the role of nursing – in today’s complex health care setting – in genuinely compassionate, patient-centered care. We also listen to the experiences of Wanda Baker, a pediatric nurse and native Canadian who has worked in critical care and palliative care in Canada and the United States.

The connection that you have with people is a connection that seals the deal, in terms of our oneness. We are bearing witness to one another. And if we are honest and open to that experience, that is where we all find our strength.”

The connection that you have with people is a connection that seals the deal, in terms of our oneness. We are bearing witness to one another. And if we are honest and open to that experience, that is where we all find our strength.”

— Wanda Baker

I find it curious in nursing that for such a deeply intimate profession and a deeply caring profession, we almost have an allergic reaction to using the word ‘love.’ Love so defines how we relate to patients and each other.”

I find it curious in nursing that for such a deeply intimate profession and a deeply caring profession, we almost have an allergic reaction to using the word ‘love.’ Love so defines how we relate to patients and each other.”

— Connie Delaney

Photo: Chungkuk-Bae

Perhaps more than any other trait in a spiritual caregiver, recipients of care yearn for the attention of an open-hearted person who can bear witness to their challenges. But what does it mean to bring that presence into an encounter with someone who may be up against adversity?

We explore this powerful realm in a remarkable dialogue with Frank Rogers, author of Practicing Compassion, recorded April 2018 at Harvard Divinity School, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (He presented the keynote talk there at our conference, “Cultivating Resilience in the Peaks and Valleys of Chaplaincy.”) Frank is professor of spiritual formation and narrative pedagogy at the Claremont School of Theology, near Los Angeles, where he co-directs the Center for Engaged Compassion, which prepares chaplains to serve in prisons and other venues.

Spiritual caregiving can offer deep personal rewards to practitioners, who are drawn to helping people undergoing distress in a wide range of settings. But by its nature, this kind of work can be emotionally and physically draining. So taking care of oneself also becomes an essential requirement of doing this work, as is discussed.

Also included is an excerpt of our Humankind documentary, previously recorded with chaplains he trained, as well as inmates incarcerated at Los Angeles County jails. That’s from our series, The Power of Nonviolence, which can be heard free at: ‘The Power of Nonviolence’

When people are in challenging situations, the most fundamental thing that they are longing for is to know that they are not alone in the midst of that – and that what their experience is, whether it’s their devastating grief, or their terror at being locked up for life in a prison.

When people are in challenging situations, the most fundamental thing that they are longing for is to know that they are not alone in the midst of that – and that what their experience is, whether it’s their devastating grief, or their terror at being locked up for life in a prison.

Whatever they’re going through can be heard, can be met, can be empathized with, and can be received with a warm, caring regard. That they can be held in that moment of pain. That’s the bottom line longing that people have in those moments. And so whatever form our caregiving takes, whether it’s as a counselor, as a chaplain in a prison or a hospital, or just as a companion, with a friend – to offer that kind of compassion meets a person at the place of their deepest longing.”

— Frank Rogers, author of ‘Practicing Compassion’

Rabbi Shira Stern in White Sulphur Springs, W. Virginia with survivor of the 2016 flood

From firefighters to police officers to the Red Cross and many others, First Responders play an essential role in protecting public safety and helping people cope with emergencies. In this segment, we consider the work of providers of disaster spiritual care. These folks look after both survivors of tragedies and the responders, who are sometimes reeling in the wake of calamity.

We hear the reflections of Rabbi Shira Stern, a long-time Red Cross volunteer (and pastoral counselor) who provides chaplaincy services in times of crisis. She’s been deployed to Ground Zero following the 9/11 attacks in New York, a flood that inundated a West Virginia community, the Boston Marathon bombing and other disasters. Her task is to listen, to offer reassurance and, importantly, to show the survivors – often frightened because their lives have been upended – that they are not alone. Rabbi Stern along with her husband leads a synagogue in Marlboro, NJ (outside New York City). She is the daughter of the late-great violinist Issac Stern, who died of unrelated causes shortly after 9/11, a time when her own mourning coincided with the nation’s.

Next we visit with Rev. James Tilbe, the pastor of the First Congregational Church, located next to the Raynham, Massachusetts Fire Department, where he serves as the fire chaplain and is also an on-call firefighter. Jim finds himself taking care of firefighters and EMTs, who sometimes witness horrific scenes in the course of performing essential duties. Jim also serves as chief chaplain of the Massachusetts Corps of Firefighters. In addition, we hear from Lt. Jeff Kelleher, a veteran of the Raynham department, who describes how firefighters process the challenges of crises in a small New England town.

Rev. Jim Tilbe, Raynham, MA fire chaplain and on-call firefighter

Lt. Jeff Kelleher, Raynham, MA Fire Department

It’s important for me to be able to reach out to people and look them in the eye, and say, ‘You’re not going to do this alone. Yes, it’s really hard. Yes, it’s really scary. No, you’re not doing this alone.’ I’m not here to be God, I’m here to represent the fact that God’s hand is here to hold you up.”

— Rabbi Shira Stern, disaster care provider with the Red Cross

As a fire chaplain I have two jobs. First of all, to be there for the firefighters, for the emergency responders who are maybe dealing with this terrible event that has just happened. And second, to be there for those that it has happened to; the homeowner, the people who were with the person that was just injured, or in the vehicle.”

— Rev. James Tilbe, Raynham, MA fire chaplain

Health care chaplaincy has increasingly been a subject of evidence-based research: What do spiritual care providers do? How do patients and their families respond to a chaplain’s services? Does spiritual care affect levels of patient anxiety and other forms of distress? To what extent do people facing illness also experience spiritual struggle (e.g. feeling abandoned by God)?

This emerging field of research reflects rising interest in best practices for spiritual care providers and growing attention to the outcomes of chaplains’ services – quality of health care, including the level of patient and family satisfaction from hospital stays. Understanding these trends has become especially relevant at a time of ever-greater complexity of health care institutions and practices (and how they are funded).

In this episode of the podcast, we review findings of some recent studies by the American Cancer Society, the Mayo Clinic, Pew and others sources. Two leading researchers offer their perspectives:

George Fitchett is professor and director of research at the Department of Religion, Health, and Human Values at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. He also serves as co-principal investigator for the Transforming Chaplaincy Project. Rev. Fitchett is author of Assessing Spiritual Needs, and co-editor of Spiritual Care in Practice.

Sociologist Karen Steinhauser, based at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, is professor of population and health sciences and professor of medicine. She’s a member of Duke Palliative Care and the Duke Cancer Institute and has led a five-year NIH study, “Trajectories of Serious Illness: Patients and Caregivers”.

[Patients sometimes report:] Having been in the hospital, hard as it was, I was pleased with the care that I received because I was listened to. Because people took my worries seriously, and tried to address them.’ So we think that that may be part of why we see this pattern of high levels of overall satisfaction for people who had chaplain visits, versus not.”

[Patients sometimes report:] Having been in the hospital, hard as it was, I was pleased with the care that I received because I was listened to. Because people took my worries seriously, and tried to address them.’ So we think that that may be part of why we see this pattern of high levels of overall satisfaction for people who had chaplain visits, versus not.”

– George Fitchett, Rush University, Chicago, IL

We asked patients and families to rate the importance of being free from pain, being at peace, a whole range of issues that we thought might be important. And, very interestingly, patients and families rated being free from pain, and being at peace as equal to one another.”

We asked patients and families to rate the importance of being free from pain, being at peace, a whole range of issues that we thought might be important. And, very interestingly, patients and families rated being free from pain, and being at peace as equal to one another.”

– Karen Steinhauser, Duke University, Durham, NC

There’s a kind of mystery in sitting calmly, patiently, attentively and tuning into someone else’s personal story – their experience and life journey.

In this segment, we hear the insights of people who, in a sense, listen for a living: physicians, counselors, clergy and others. What does it mean to set aside one’s own agenda and truly focus on another person, perhaps someone who is suffering?

Says best-selling author Joan Borysenko, who’s written on neuroscience and now practices as a spiritual director in Santa Fe, New Mexico, listening with generous compassion activates the “affiliation” systems in our brain. The mind becomes happy or focused at the deep connection. “When I’m listened to deeply, I relax and move out of the stressful part of myself – the part that maybe wants to defend something, and into a part of me that has the courage simply to be honest, and to be myself.”

We also consider the experience of James Gordon, MD, clinical professor of psychiatry and family medicine at Georgetown University Medical School in Washington. He does a lot of listening in his work with traumatized children and their families facing crisis. We hear the story of survivors of the 2017 hurricanes that battered residents of Puerto Rico; and people who lived through horriffic war in Kosovo in the mid-1990s. Said a family member who lived through atrocities in the war: “We know that you are listening to us, and we know that you are going to share our story with others. And that is all we could hope for. That’s all we want.”

A chaplain at El Camino Hospital near San Jose, California, Rev. John Harrison, tells the story of encountering a patient who was a little rough around the edges. He recalls entering “one of the most brilliant conversations I’ve ever had about life and the meaning of life” which arose when he abandoned talk of religion and listened to the patient in his care.

One of the greatest acts of generosity is to be able to listen to another person without judgment – without getting your own views, opinions, and biases in the way.”

One of the greatest acts of generosity is to be able to listen to another person without judgment – without getting your own views, opinions, and biases in the way.”

–Joan Borysenko, best-selling author on the mind/body connection, Santa Fe, NM

What’s important is creating the state of being in which it’s actually possible to listen, first of all, to yourself, and then to another human being.”

What’s important is creating the state of being in which it’s actually possible to listen, first of all, to yourself, and then to another human being.”

–James Gordon, MD, psychiatrist, Washington, DC

I think that the act of listening is a sacred act that requires us to empty ourselves of ourselves so that we can be fully present to another. Active listening is not waiting for one’s turn to speak.”

I think that the act of listening is a sacred act that requires us to empty ourselves of ourselves so that we can be fully present to another. Active listening is not waiting for one’s turn to speak.”

–Rev. John Harrison, director of spiritual care, El Camino Hospital, Mountain View, CA

This episode considers the need to carve out an experience of silence in our own lives – as a basis for attentively listening to others. But actually setting aside quiet time can be hard for many of us. It may feel uncomfortable at times and we’re susceptible to distractions, especially amid all the electronic communication coming at us. Our attention can be diverted, even when we have a sincere intention to listen compassionately to another.

Joan Borysenko, Santa Fe-based author of Minding the Body, Mending the Mind and many other books on the mind-body connection, points out that self-regulation techniques, such as deep breathing, can help to settle us down. “We’re a culture,” she observes, “that is big on doing, and not so big on the joy and the importance of just being.”

Irene Harris, a therapist with the VA Health Care system in Minneapolis, comments that some professionals can get caught up in “the self-evaluative monitor” where they focus more on their own performance, than on attending to the needs being expressed by the person in their care.

Physician James Gordon, founder of the Center for Mind Body Medicine in Washington, DC, adds that distraction can be a sign that there’s some personal business the listener needs attend to, or that the person being cared for has gotten stuck and needs help in getting Unstuck, the title of his recent book.

Joan Borysenko adds a description of “meta-awareness”, in which we become conscious of our own (sometimes very distorted) thoughts. This can allow us to avoid being hijacked by them. “I’m going to take a breath, and just notice: what am I thinking? How does it affect my body? And is it really true? Can I back up from that?” These are all essential practices in clearing mental space to be available to someone we’re listening to.

Finally, Jim Gordon considers the process of relaxing when we face a situation that is stressful or even baffling. “I need to surrender, and I’m surrendering to the universe, to God, giving up my expectations, my beliefs, my roles, and just being present. So it’s really a question of letting go.”

If you find yourself being distracted, you take a couple deep breaths, and you come back, and be present again.”

If you find yourself being distracted, you take a couple deep breaths, and you come back, and be present again.”

– James Gordon, MD, psychiatrist and integrative medicine pioneer, Washington, DC

We have to find a way to make this interaction not about what a great therapist I am, but about the inherent spiritual value, and dignity, and worth of the person who is coming to us for help.”

We have to find a way to make this interaction not about what a great therapist I am, but about the inherent spiritual value, and dignity, and worth of the person who is coming to us for help.”

– Irene Harris, psychologist, Minneapolis VA Health Care

Would you give us 2 minutes of your time to take our quick survey? It will help us learn how The Spiritual Care Podcast can be of service to you and others — and to improve! Thanks.

Would you give us 2 minutes of your time to take our quick survey? It will help us learn how The Spiritual Care Podcast can be of service to you and others — and to improve! Thanks.

The survey is available here.

National Association of College and University Chaplains

Vanderbilt University Office of Religious Life

The Army Chaplain who resigned over the military drone program

On Living by Kerry Egan, Riverhead Books, 2016 (Penguin Random House)

Written and produced by DAVID FREUDBERG

Studio recording by NOEL FLATT and DOUG SHUGARTS

Editorial support by David Cruz, Cathy Graham, Maggie Mantus, Ken Rogers, Andrew Andresco and Brian K. Johnson

© 2018 Human Media

Presented in association with the BTS Center. Funding generously provided by the Henry Luce Foundation and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.