The Power of Nonviolence

Programs 231, 232, 235, 236, 244, 245, 248, 249 • 4 hrs

CDs available via special order. HumanMedia ®

Also available on our Podcast

Programs 231, 232, 235, 236, 244, 245, 248, 249 • 4 hrs

CDs available via special order. HumanMedia ®

Also available on our Podcast

Mohandas Gandhi, the great spiritual leader from India, famously observed: “An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.” History proves over and over that violence breeds more violence. Victims are traumatized by brutality — as are perpetrators, and the cycle is uninterrupted.

Yet, today terrible shootings erupt repeatedly, as do episodes of police-involved violence. People of conscience everywhere are heartsick and looking for answers. As Rev. Martin Luther King declared, “There is another way.”

The Power of Nonviolence, a timely new public radio project from Humankind, seeks deep solutions to this vexing problem. We turn to wisdom teachings across our great spiritual traditions for guidance — and inspiration — on how the lasting wounds can be healed.

As you’ll hear, some of their stories are vivid and quite uplifting. Their insights may even be life-changing.

We encourage you to share these programs and to discuss them with loved ones and members of your community and congregation. Additional programs are in the pipeline, as well.

How do we stop the epidemic of violence?

The Power of Nonviolence, a timely new public radio project from Humankind, seeks deep solutions to this vexing problem. We turn to wisdom teachings across our great spiritual traditions for guidance—and inspiration—on how the lasting wounds can be healed.

And we hear from peacemakers today who, against many obstacles, are building a world where children can grow up safe and we can all live without fear. As you’ll hear, some of their stories are quite uplifting.

We encourage you to share these programs and to discuss them with loved ones and members of your community and congregation.

The world was stunned in the storied southern city of Charleston, South Carolina on a summer’s night in 2015. The unthinkable had happened: a young gunman consumed by hate suddenly opened fire during a quiet Bible study group at an historic African American church. He left nine dead, including the church’s pastor and an 87-year-old woman. And yet in court two days later, the surviving families, in deep grief, voiced forgiveness toward the young man. They did not excuse his murderous actions, but as one relative put it: “We are a family that love built. We have no room for hate.” It was a breathtaking scene. Perhaps it contributed to the atmosphere in which the Confederate flag finally came down in South Carolina and other southern states. And the families’ forgiveness added a “counter-cultural” ingredient to the story of how we respond to violence.

The world was stunned in the storied southern city of Charleston, South Carolina on a summer’s night in 2015. The unthinkable had happened: a young gunman consumed by hate suddenly opened fire during a quiet Bible study group at an historic African American church. He left nine dead, including the church’s pastor and an 87-year-old woman. And yet in court two days later, the surviving families, in deep grief, voiced forgiveness toward the young man. They did not excuse his murderous actions, but as one relative put it: “We are a family that love built. We have no room for hate.” It was a breathtaking scene. Perhaps it contributed to the atmosphere in which the Confederate flag finally came down in South Carolina and other southern states. And the families’ forgiveness added a “counter-cultural” ingredient to the story of how we respond to violence.

This program examines our responses. It places the Charleston churchgoers in the context of the African American Christian tradition in the south, where the nonviolent example of Jesus is central. And we hear from long-time civil rights activist, Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, now a religion professor at the Univ. of Florida.

We also hear from Jack Kornfield, a Buddhist teacher and best-selling author. As a young man he entered the Peace Corps and was assigned to Cambodia — at the time of the genocide that came to be known as “killing fields.” He relates the moving story of a Buddhist teacher (the “Gandhi figure” of Cambodia), who invoked the healing power of love to mend the hearts of survivors who’d suffered unspeakable loss.

Includes songs performed for this series by Noel Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul and Mary.

Somebody must have sense enough to meet physical force with soul force. If we will but try this way, we will be able to change these conditions and yet, at the same time, win the hearts and souls of those who have kept these conditions alive.”

Somebody must have sense enough to meet physical force with soul force. If we will but try this way, we will be able to change these conditions and yet, at the same time, win the hearts and souls of those who have kept these conditions alive.”

—Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As long as you’re holding on to feelings of resentment and hatred, no question it corrodes you.”

As long as you’re holding on to feelings of resentment and hatred, no question it corrodes you.”

—Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons

Hatred never ceases by hatred, but by love alone is healed. This is the ancient and eternal law.”

Hatred never ceases by hatred, but by love alone is healed. This is the ancient and eternal law.”

—Jack Kornfield, (R), Buddhist teacher and best-selling author

We hear stories of peacemakers who draw from their lives and traditions as a basis for breaking down barriers and promoting conflict resolution. An Episcopal priest Charles Gibbs, now in the Washington, DC area, has dedicated his life to peace-building endeavors, including a global interfaith organization. His early awareness of the need to establish connections developed through lessons he learned growing up with an intellectually-challenged brother.

Rev. Kristin Stoneking, tells the story of growing up in a Methodist Mennonite congregation, a “peace church”. Her father was a pastor in Kansas City. The family practiced three dimensions of Gandhian nonviolence: personal transformation, spiritual transformation and social action. Today Kristin is Executive Director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an interfaith pacifist organization founded just prior to WW1, which popularized the adage: “There is no way to peace, peace is the way.”

Quaker author Eileen Flanagan, attends another peace church, a Quaker congregation in Philadelphia, a city with a well-established heritage of Quakerism dating back to colonial times. The idea that “there is that of God in every person” is a guiding principle, that can make reconciliation of differences more practical.

Michael Lerner, the editor of Tikkun magazine and rabbi of Beyt Tikkun synagogue in Berkeley, California, says that all religions and all people are engaged in an internal struggle of worldviews — between a life of fear (and a perceived need to dominate others) and one based on love, which leads to caring for others. He draws upon deep study — in addition to being an ordained clergyman, Michael earned doctorates in philosophy and in psychology.

M.R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, the late Sufi sage, led a remarkable life based on humanity and service. And he taught a perspective on Islam that may surprise people who are accustomed only to the most menacing stereotypes of Muslims. Bawa explained that, at its essence, Islam is nonviolent and that in perceiving others as “enemies,” we are really projecting onto them our own hateful thoughts. The solution is to think deeply and chase away our own tendency to hatred.

[My disabled brother] taught me, at the deepest level possible, that there are no ‘other’ human beings. We’re all related, we’re all sisters and brothers to each other and our job here is to live into that.”

[My disabled brother] taught me, at the deepest level possible, that there are no ‘other’ human beings. We’re all related, we’re all sisters and brothers to each other and our job here is to live into that.”

—Rev. Charles Gibbs

National Cathedral, Washington, DC

If we’re acting out of a place of compassion, it’s going to bring out the best in someone else, rather than being agitated or unsettled in a way that brings out the anxiety in them.”

If we’re acting out of a place of compassion, it’s going to bring out the best in someone else, rather than being agitated or unsettled in a way that brings out the anxiety in them.”

—Eileen Flanagan, Quaker author

There’s a deep commitment in the spiritual and religious worlds to a view of human beings as fundamentally sacred. And consequently, in dealing with every human being we have to imagine that we are in God’s presence.”

There’s a deep commitment in the spiritual and religious worlds to a view of human beings as fundamentally sacred. And consequently, in dealing with every human being we have to imagine that we are in God’s presence.”

—Rabbi Michael Lerner, Editor of Tikkun magazine, Beyt Tikken synagogue

In order to take on violent systems, it’s really important to have a community of support to remind you what you believe in.”

In order to take on violent systems, it’s really important to have a community of support to remind you what you believe in.”

—Rev. Kristin Stoneking, Fellowship of Reconciliation

If one knows the true meaning of Islam, there will be no wars. All that will be heard is the sounds of prayer and greetings of peace. Only the resonance of God will be heard, not the battle cries.”

If one knows the true meaning of Islam, there will be no wars. All that will be heard is the sounds of prayer and greetings of peace. Only the resonance of God will be heard, not the battle cries.”

—M.R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, Sufi master and author of “Islam and World Peace”

In a world afflicted with so much violence, it would be easy to underestimate the impact of basic human compassion in actually solving conflict. Yet time and again, people are transformed—sometimes profoundly—by gentle acts of caring. Mere gestures of sympathy may not be effective in the heat of a battle, but in many settings compassion has a remarkable capacity to defuse antagonism. In this segment, we hear theologian Frank Rogers, whose personal struggle with rage in reaction to a tough childhood drove him to analyze the dynamics of compassion. In his book The Practice of Compassion, Rogers concluded: There are specific skills that can be cultivated in people seeking to enhance their own compassion.

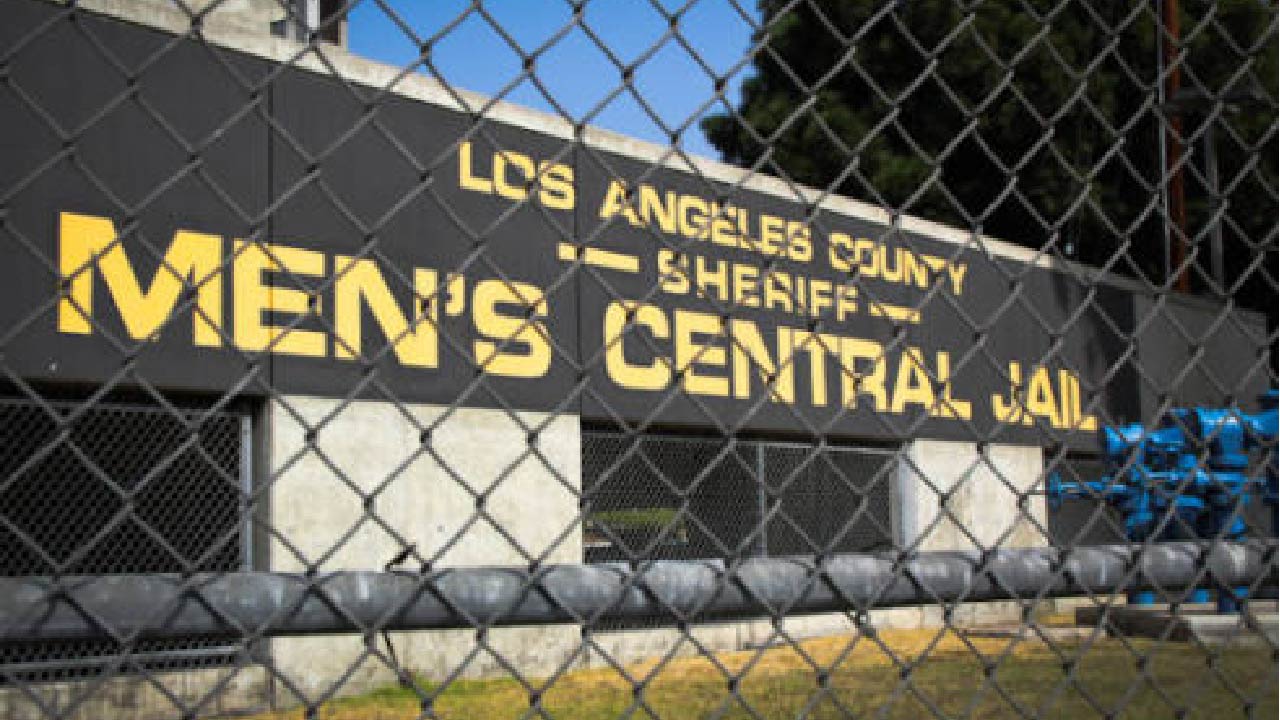

We travel to two Los Angeles jails, including one of the world’s largest, Men’s Central Jail. A prison chaplain there, Brother Dennis Gibbs, an Episcopal deacon, was once himself an inmate. He now reaches out to prisoners who volunteer for compassion training. We listen in on one of his classes and talk with Br. Dennis as well as an inmate whose remarkable tale of self-reflection lays the groundwork for a successful life after incarceration.

From there we venture to a women’s jail, Century Regional Detention Facility. We learn about the vicious cycle of shame and violence in which many prisoners are caught up. Sister Greta Ronningen, who founded an Episcopal monastery in the Benedictine tradition, leads a meditation with two young prisoners. And we hear about their efforts to apply compassion in interactions with other inmates, who may be grumpy amid the intense strain of incarceration.

These jailhouse chaplains were both trained by Frank Rogers at the Claremont School of Theology, east of Los Angeles. He emphasizes taking stock of ways in which all of us have been the recipients of caring by others, whether by a relative early in life or by sympathetic friends later on. And even for those people who feel utterly abandoned, merely developing self-compassion may be deeply healing.

Br. Dennis Gibbs, prison chaplain

Why do our hearts sometimes harden and impede the flow of compassion? Getting a handle on this question requires deep awareness of the underlying impulses that drive our shifting moods. Compassion teacher Frank Rogers suggests that our fears, obsessions, angry attitudes and stress reactions are often an expression of “some deep need that is aching to be tended,” some old, open wound. If we can develop a conscious distance from these mental fluctuations, we may be better able to recognize our drives, rather than feel threatened by them. We therefore can soften our reactions to the world, and draw from a reservoir of inner compassion for others.

So how does this attitude affect the way we see and interact with others? Muslim imam Haytham Younis highlights the basic decorum of maintaining social civility “with everyone, even if someone is not polite to me. I try to remain polite and gentle.” And behaving this way with others, he notes, brings us natural blessings, like the health effects from peace of mind.

Buddhist meditation teacher Jack Kornfield tells of young nuns from Tibet who were cruelly persecuted and tortured, but whose greatest fear was that their own hearts would coarsen in response, thus yielding to the hatred they stood against. And we hear the story of an army colonel who, surrounded by a large, hostile crowd, ordered his men to kneel down in a gesture of respect and peace, thus soothing a tense situation that could easily have blown up.

UCC minister Rev. Betty Stookey emphasizes the importance of a calming discipline, like meditation. She also says we must act intentionally to break down social barriers, because “if you have somebody in your house for dinner, you’re not going to throw stones at them tomorrow.” And Rabbi Michael Lerner comments that—rather ¬†than rejecting people who show an anti-social side—we can view them as wounded, and set as our focus an attempt to help them heal.

[When people are] incapable of identifying with the suffering of poor people, and hungry people in this world, and the immigrants, and so forth. I’m not going to say they’re wrong… I’m going to say they’re deeply wounded. And what can we do to unwound them?”

—Rabbi Michael Lerner

It’s a vast spider web. When we say something to someone else, whether it’s kindness, or whether it’s hatred, that thought makes the whole spider web tremble… And then you don’t know in what far place your message is being felt… We are all so connected.”

It’s a vast spider web. When we say something to someone else, whether it’s kindness, or whether it’s hatred, that thought makes the whole spider web tremble… And then you don’t know in what far place your message is being felt… We are all so connected.”

—Rev. Betty Stookey (with her husband, famed folksinger Noel Paul Stookey, who performs his moving ballad, ‘Facets’)

You have many ways to connect with the spirit force of God so that you are able to be steadied, and not let the forces of anger, or rage, or hatred take over. You have to be involved, hopefully, with a community of believers, and people who are practitioners.”

—Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons

If God is merciful and compassionate, then he loves mercy and compassion… If I am to follow the way that God would like to see me follow, then I must try also to be merciful and compassionate.”

If God is merciful and compassionate, then he loves mercy and compassion… If I am to follow the way that God would like to see me follow, then I must try also to be merciful and compassionate.”

—Haytham Younis

Note: To hear this program now, click on the Listen tab above.

Note: To hear this program now, click on the Listen tab above.

How exactly can we build a future based on understanding and connection among people of diverse backgrounds — rather than prejudice, misinformation and suspicion that are the fuel for violence? According to the late journalist John Wallach, the answer is to instill this awareness at a young age. He went on to found a truly daring experiment in breaking down barriers: the Seeds of Peace summer camp on a glistening lake in Otisfield, Maine. David paid a return visit for this episode. Since the camp was launched in 1993, more than 6,000 teenagers from conflict regions around the globe have come for about a month of refuge. Their homes are in places like the Middle East and South Asia. Usually it’s their first encounter with someone from “the other side” of bitter religious, ethnic or national discord. Here they meet, talk, eat, play sports, and sing together, living in integrated bunks. They discover that people who’ve been demonized are not monsters — just other kids trying to make their way in a confusing world.

We hear the diverse voices and accents of campers, who are known as the Seeds. They are Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, Christian, agnostic, etc. and are invited into interfaith dialogue. They are disturbed by violence, especially when claimed to be perpetrated on “religious” grounds. They feel they are up against a wall of misinformation disseminated by media in one country against the people of another.

Camp co-founder Bobbie Gottschalk, who remains active in Seeds of Peace, recalls her own experience as a 20-year-old student at a Quaker college, which organized a trip to the Soviet Union to promote person-to-person dialogue at the height of the Cold War. That journey helped her understand the importance of forging personal connections in a polarized world.

As one counselor observed: “Understanding and being able to open your ears to the other side can make a world of change.”

There are a lot of people who just plain don’t like the idea of Seeds of Peace. It’s more comfortable to just stay partisan, and you know who you are… You have a certain kind of religion, you have a certain kind of political view, and you have a certain kind of goals in life. And they don’t want to see people changing.”

There are a lot of people who just plain don’t like the idea of Seeds of Peace. It’s more comfortable to just stay partisan, and you know who you are… You have a certain kind of religion, you have a certain kind of political view, and you have a certain kind of goals in life. And they don’t want to see people changing.”

—Bobbie Gottschalk, co-Founder

I came to make friendships with people from the other side… I felt like I was living in a bubble, and it suddenly popped.”

I came to make friendships with people from the other side… I felt like I was living in a bubble, and it suddenly popped.”

—Camper (Israel)

We are told to see the other country as being one unit. However, when we come to Seeds of Peace we realize that it’s not always that the people agree with the decisions taken by their own government. And that’s why it’s very important for us to also see the people just as fellow human beings.”

We are told to see the other country as being one unit. However, when we come to Seeds of Peace we realize that it’s not always that the people agree with the decisions taken by their own government. And that’s why it’s very important for us to also see the people just as fellow human beings.”

—Camper (India)

Where else in the world are you going to get Israelis and Palestinians sitting in a room together? And then afterwards to go out and play soccer together, and do activities. At the end of the day what you realize is that we’re not so different.”

Where else in the world are you going to get Israelis and Palestinians sitting in a room together? And then afterwards to go out and play soccer together, and do activities. At the end of the day what you realize is that we’re not so different.”

—Camper (U.S.)

It’s not right for people to go around killing innocents, and saying that, you know, ‘Yeah, we’re doing it because God wants us to,’ because God doesn’t, in my—in my opinion, I don’t think God wants you to do that.”

—Camper (Pakistan)

When we’re in a disagreement, it’s sometimes hard simply to listen to the other person. The emotional temperature may be high and we can shut down in a defensive posture. But skillful listening is a core practice of conflict resolution and, potentially, a doorway to improved relations, greater self-understanding, and personal growth.

When we’re in a disagreement, it’s sometimes hard simply to listen to the other person. The emotional temperature may be high and we can shut down in a defensive posture. But skillful listening is a core practice of conflict resolution and, potentially, a doorway to improved relations, greater self-understanding, and personal growth.

Here we explore some principles of deep listening. We hear the rich reflections of Betty Burkes, a peace educator and Buddhist practitioner, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She emphasizes the value of pausing long enough just to notice what you’re actually feeling in conflict. What are you reacting to? This shifts the spotlight from the words and actions of the other person to one’s own experience. It can promote self-reflection and healing. Burkes embraces a philosophy known as Nonviolent Communication, which was developed by the late Marshall Rosenberg, PhD, whom we profiled in Humankind program #100. She also probes ways out of the dilemma that results when pain triggers as anger.

Then, we examine a search for common ground between two friends in the Washington, DC area: Daniel Spiro, a Jewish attorney and novelist and Haytham Younis, a Muslim imam (prayer leader). Together they co-founded the Jewish Islamic Dialogue Society (JIDS), which convenes monthly discussions drawing on members of various synagogues and mosques.

When asked for commonalities among Jews and Muslims, members identified these “unifiers”: being a minority group in America; ultimate values they share: charity, justice, peace, truth, humility and gratitude; as well as similar language and customs. And although often depicted as being seriously at odds, there’s another bond between these two groups: their embrace of monotheism— the ancient belief in a single, universal higher power.

Say you’re in a situation that is conflictual, like you’ve gotten really riled up about something. This is what happens to me: something cautions me, and I pause. It’s like allowing yourself to be empathetic, allowing yourself to just be with what’s happening. Like feel your heartbeat, which is racing by then. So you relax, and then you notice what comes up. Trust what’s emerging.”

Say you’re in a situation that is conflictual, like you’ve gotten really riled up about something. This is what happens to me: something cautions me, and I pause. It’s like allowing yourself to be empathetic, allowing yourself to just be with what’s happening. Like feel your heartbeat, which is racing by then. So you relax, and then you notice what comes up. Trust what’s emerging.”

—Betty Burkes, peace educator

In the suffering, and the harm, and the hurt, and the injustice that both sides feel they’ve endured, there is something very connecting about that. The realities of both sides are reflected in each other’s reality.”

—Betty Burkes

If you want to be a better Jew, study Islam and you’ll find plenty with which to fall in love; if you want to be a better Muslim, study Judaism, and you too will find plenty with which to fall in love. These faiths beautifully complement each other.”

If you want to be a better Jew, study Islam and you’ll find plenty with which to fall in love; if you want to be a better Muslim, study Judaism, and you too will find plenty with which to fall in love. These faiths beautifully complement each other.”

—Daniel Spiro, co-founder of JIDS

I remember going to a high school and asking the students, with regards to people outside of their faith tradition: who do they associate with? And I always find that the Muslim students and the Jewish students gravitate towards each other. And there’s a deep understanding there about religion.”

I remember going to a high school and asking the students, with regards to people outside of their faith tradition: who do they associate with? And I always find that the Muslim students and the Jewish students gravitate towards each other. And there’s a deep understanding there about religion.”

—Haytham Younis, co-founder of JIDS

Note: brief moments contain graphic descriptions of war.

Following more than a decade of war, up to 400,000 returning U.S. soldiers bring with them invisible wounds. After war, our veterans face a new battle: emotional and spiritual conflict that is normal to human beings who’ve experienced intense brutality.In the Civil War this condition was called “soldier’s heart”, in WW1 it was known as “shell shock”, and today many veterans are diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

In this half-hour segment (and also in Part 8), we examine the effects of military violence and how people begin the journey of healing from it. We hear deeply moving stories of veterans who served in Iraq, Afghanistan and Vietnam. Back home, they may be prone to outbursts of anger or withdrawing emotionally, as well as addiction to alcohol and other drugs. These patterns can perpetuate the impact of violence. And some vets may be tempted to harm others— or themselves.

In trying to put their lives back together, some now participate in counseling and attend support groups with other vets. They may practice relaxation techniques, like meditation. Some have become antiwar activists. Others join volunteer activities to help refugees from war zones.

I sat there, and I think I smoked a pack of cigarettes by myself, and I could feel a change in me… Nothing that prevented doing my job, but something changed.”

I sat there, and I think I smoked a pack of cigarettes by myself, and I could feel a change in me… Nothing that prevented doing my job, but something changed.”

—Kyle M., National Guard member, who survived bloody ambushes in Afghanistan

I knew that other people didn’t like Vietnam veterans, and I didn’t like myself. So my strategy was to basically repress that whole thing, like it never happened. It doesn’t work.”

I knew that other people didn’t like Vietnam veterans, and I didn’t like myself. So my strategy was to basically repress that whole thing, like it never happened. It doesn’t work.”

—Bill Simon, U.S. aircraft crew chief, Vietnam War

For years I just hated— it was like battery acid— the Iraqis. I mean, they pick you off. But letting go of that anger, working with the Iraqi refugees in Massachusetts, it was cathartic.”

For years I just hated— it was like battery acid— the Iraqis. I mean, they pick you off. But letting go of that anger, working with the Iraqi refugees in Massachusetts, it was cathartic.”

—Travis Weiner, served 2 U.S. Army tours in Iraq

I think the first step is for someone they can trust, to be a trustworthy friend… And that’s generally another veteran, but not always.”

I think the first step is for someone they can trust, to be a trustworthy friend… And that’s generally another veteran, but not always.”

—Prof. Rita Nakashima Brock, author, Soul Repair

You have to say: I don’t know everything about why this has happened to me, but I believe that there is the ability to have a positive, caring, nurturing, loving response come out of this.”

You have to say: I don’t know everything about why this has happened to me, but I believe that there is the ability to have a positive, caring, nurturing, loving response come out of this.”

—Wayne Jonas, M.D., Lt. Colonel (retired), Army Medical Corps

Note: brief moments contain graphic descriptions of war.

In this documentary, we explore what it’s like to experience “moral injury”— when soldiers witness or participate in war-time acts that violate their conscience. The impact they undergo confirms an enduring truth: on the battlefield, everyone is a victim.

How does one come to terms with a deeply painful incident from the past? When deep regret sinks in, how do people wrestle with what happened and find a way to peace?

Often, this process raises life questions that force us to seek spiritual answers. One veteran, a former U.S. counter-intelligence agent in Afghanistan, suffered severe PTSD symptoms, including migraines and sleep deprivation. He discusses overcoming an initial reticence to get help. Ultimately, he reached out to the chaplain service at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in his home town, Washington, D.C. But recovery is often a protracted process.

Often, this process raises life questions that force us to seek spiritual answers. One veteran, a former U.S. counter-intelligence agent in Afghanistan, suffered severe PTSD symptoms, including migraines and sleep deprivation. He discusses overcoming an initial reticence to get help. Ultimately, he reached out to the chaplain service at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in his home town, Washington, D.C. But recovery is often a protracted process.

We also hear from two of the chaplains, who’ve spent many hours listening to vets and helping them think through this difficult dilemma.

In addition, see our Peace Studies tab (above) to hear web-only audio on this theme, including comments by theologian and author Shelly Rambo, as well as further explanations from VA counselor Daniel Libby.

You’ll hear stories that will break your heart, and my heart is broken, many times. But I always believe God is right there with us in the suffering.”

—Rev. Cheryl Jones (R), Veterans Administration chaplain

When you get home, and you look back, and like: Who am I? That person who decided this other person needed to die?”

—Rev. Carol Ramsey-Lucas (L), Veterans Administration chaplain

You’re watching some of the worst horrors that are known, and you ask yourself: you know if there’s a God out there, how can he allow this stuff to happen?”

You’re watching some of the worst horrors that are known, and you ask yourself: you know if there’s a God out there, how can he allow this stuff to happen?”

—Manny Salazar, Afghanistan vet

Some of the men and women that I’ve worked with who have done some horrible things, they’re not horrible people. They isolate themselves because they don’t want to hurt anybody else.”

Some of the men and women that I’ve worked with who have done some horrible things, they’re not horrible people. They isolate themselves because they don’t want to hurt anybody else.”

—Daniel Libby, VA counselor, founder of Veterans Yoga Project

Check out these excellent resources for more information